SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

| Aerial drone footage shows flooding caused by Hurricane Florence in Ringlewood, N.C., Sept. 17, 2018. Hurricane scientists estimated that global warming boosted Florence’s rainfall by more than 50%. Photo: North Carolina National Guard, Flickr Creative Commons. Click to enlarge. |

Feature: How Climate Attribution Science Went Mainstream, and What It Means

By Bob Berwyn

The science of finding global warming fingerprints on climate extremes has come so far in the past few decades that we now know that some recent deadly heat waves, floods and other climate extremes probably never would have happened without the extra heat trapped by greenhouse gases.

One such extreme: The June 2021 heat storm that killed hundreds of people in the Pacific Northwest.

Climate attribution researchers have also shown that global warming intensified the rainfall from Hurricane Harvey by up to 18%. The storm killed 80 people in 2017 when it swamped the Houston area with up to 50 inches of rain.

And in 2018, hurricane scientists estimated that global warming boosted Hurricane Florence’s rainfall by more than 50% (the storm ultimately produced record-breaking rainfall across portions of the Carolinas, including 30-plus inches in some North Carolina locations).

As climate attribution studies proliferate, it’s not accurate any more to ask whether global warming caused a given drought or wildfire. Based on what we know now, the better questions are: How does global warming change the intensity or the probability of dangerous climate extremes? And how can we use that understanding to protect people, property and ecosystems?

The most recent science report from

the IPCC says it’s “virtually certain”

that global warming worsens

extremes like heat waves and floods.

After assessing the growing body of climate attribution science, the most recent science report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says it’s “virtually certain” that global warming worsens extremes like heat waves and floods. That report also makes it clear that their severity will increase in the years ahead, and get much worse in the second half of the century, unless we stop cooking the planet. [Editor’s Note: See Berwyn’s recent writeup about the IPCC report in SEJournal.]

The previous IPCC report, published in 2014, characterized attribution science as promising, but uncertain. In this year’s edition, by contrast, the authors wrote: "On a case-by-case basis, scientists can now quantify the contribution of human influences to the magnitude and probability of many extreme events."

Wildfires, crop-killing freezes, also linked to global warming

Even in areas that the most recent IPCC report didn’t specifically address, there are studies showing the links between global warming and damaging climate extremes.

In the western United States, for example, forest researchers have shown that global warming worsens wildfires by lengthening the season and drying out trees and brush.

There are even attribution studies showing that global warming increases the chances of damaging spring frosts destroying orchard and vineyard crops — but not because it’s getting colder. Instead, a trend toward warmer temperatures in late winter and early spring is prompting fruit trees to bloom earlier, which makes them vulnerable to subsequent damaging frosts that still can occur in a warming climate.

In the bigger climate science picture, the conclusions aren’t a big surprise. The concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is trapping the sun’s heat energy at a rate equivalent to the energy of five Hiroshima-size atomic bombs exploding each second.

The average global temperature has increased by about 1.8 F since 1850. The increase is double that over many land areas, and the Arctic has warmed three times as much.

We are already living in a

fundamentally altered climate

and scientists can see the effects

of those changes on a large scale.

We are already living in a fundamentally altered climate and scientists can see the effects of those changes on a large scale, most obviously in the melting polar ice caps, but also in shifts of ocean currents and wind patterns that shape the distribution and persistence of extremes.

Knowing that global warming will make heat waves more frequent and intense can help communities develop plans to protect vulnerable people, and show the urgency of adopting mitigation measures to try and prevent the worst impacts.

Similarly, understanding that hurricanes and other storms will deliver more intense rains can help communities plan infrastructure like roads, bridges and drainage systems.

Teasing out the clues

Climate attribution science typically uses computer simulations to analyze long-term records of temperature, rainfall and other data in a region where a climate extreme happens. By comparing models with and without the effect of warming, scientists can show how hot a heat wave would have been, or how much rain a storm would have dumped, in a climate unaltered by greenhouse gases.

|

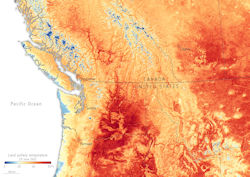

| Surface temperatures in the Pacific Northwest during a summer 2021 heat wave. Image: European Space Agency, using modified Copernicus Sentinel data, Flickr Creative Commons. Click to enlarge. |

There are also other types of attribution studies. In 2017, researchers analyzed greenhouse gas emissions country by country to determine proportionate shares of responsibility for extreme climate events, using a 2013-14 heat wave in Argentina as an example. They showed that the total warming effect of U.S. emissions had increased the probability of the Argentine heat wave by 34%, while emissions from the European Union upped the odds of the extreme heat by 37%.

Friederike Otto, lead author of that study and a pioneer of attribution research, said those estimates are useful in the context of global climate justice because the historical cumulative emissions from developed countries are having the worst effects on developing countries, which have less money to protect themselves from climate extremes.

Under the 2015 Paris Agreement, developed countries pledged to try to address that inequity. Knowing who is responsible for which emissions is a step in that direction.

Attribution science heads to the courts

In at least one case, that type of attribution has become a potentially key legal tool in legal proceedings centered on climate impacts.

In 2015, Peruvian farmer and guide Saúl Luciano Lliuya filed a lawsuit in a German district court to try to force RWE, a giant coal company, to pay for part of a wall that could protect his town from a flood threat looming because global warming is melting the glaciers above.

In the case, Lliuya claims RWE is responsible for about 0.5% of all global emissions and is asking the court to order the company to pay 0.5% of the cost of the wall. The case has been delayed by the coronavirus pandemic, but in preliminary hearings the court has shown a willingness to hear the case.

An attribution study published February 2021 could solidify the case against RWE because it shows human-caused warming is responsible for about 85% of the glacial melt above Huaraz, Lliuya’s Andean community, where up to 50,000 people in the town and surrounding areas are threatened by inundation.

Such court actions were part of what Otto had in mind when she jump-started the field of climate attribution in 2014. For too long, climate scientists have been on the defensive, asked to prove again and again what is already widely known and accepted.

But as Otto wrote in her 2020 book, “Angry Weather: Heat Waves, Floods, Storms, and the New Science of Climate Change,” attribution science enables climate scientists to go “on the offensive,” showing people that the threat of global warming isn’t in the distant future, but that it’s here now, killing people and devastating livelihoods.

Bob Berwyn is an Austrian-based freelance reporter who has covered climate science and international climate policy for more than a decade. Previously, he reported on the environment, endangered species and public lands for several Colorado newspapers, and also worked as editor and assistant editor at community newspapers in the Colorado Rockies.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 6, No. 35. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.