SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

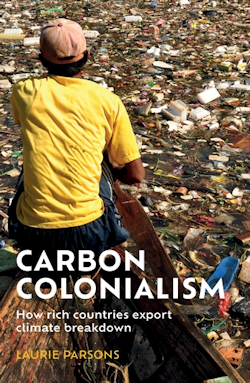

BookShelf: ‘Carbon Colonialism’ Details the Exporting of Degradation, Climate Collapse

“Carbon Colonialism: How Rich Countries Export Climate Breakdown”

By Laurie Parsons

Manchester University Press, $24.99

Reviewed by Melody Kemp

|

Years ago, I worked in occupational health and safety, a discursive cousin of environmental health. And I found myself caught up in the Asian “corporate social responsibility” movement, inspecting factories subcontracted by big-name producers like Nike, Zara, Levi Strauss, Apple and Adidas.

It became clear that such visits were like olives on a pizza: designed to add a tart publicity and a marketing tang to what was a deliberate attempt to reduce costs and substitute for official regulation.

Corporate social responsibility, I came to feel, was simply the privatizing and corruption of labor standards by corporate power.

It seems many agree with me. The fabulous and much-needed book, “Carbon Colonialism: How Rich Countries Export Climate Breakdown,” starts on a familiar note: the outsourcing of production leading to environmental and climate chaos.

But the tangent is vastly different and one I can relate to, having lived in Asia.

Are we really ‘all in this together’?

The climate change debate is now so focused on fossil fuels and mining (see COP28) that its complexity in economic, political, neo-colonial and social terms is overlooked. So this book is full of information that may seem distant from your beat.

For example, the clothing and footwear industry is one that is hugely outsourced, along with its waste and lousy wages. Cambodia, where this book is largely centered, has some of the highest electricity prices in the world.

The solution for makers of high-end clothing? Steam irons driven by burning timber. Despite the burning of forest wood being outlawed in 2018, trucks laden with freshly cut timber fuel generators that produce power for the steam irons. The trucks ply roads deep into the night.

So while industries such as

mining and metal processing are

outsourced, the environmental

cost is borne by locals.

So while industries such as mining and metal processing are outsourced, the environmental cost is borne by locals. The garment industry, in this instance, contributes between 5% and 10% of global emissions. Yet it did not rate a mention at COP28.

The much-vaunted phrase, “We are all in this together,” belies the reality that large companies outsource in virtually all high-emissions industries, thereby reducing their costs, while raising fuel and carbon consumption.

So no, we are not in it together while companies hide the origin of their goods.

The author, Laurie Parsons, a senior lecturer in the geography department at Royal Holloway, University of London, in Egham, England, uses Cambodia as his witness for the prosecution. Forests are being clear-cut for hotels and other types of development.

A chant of poverty reduction that started in the West is now increasingly used by China and other nations to destroy existing social structures and build dependency.

The book’s section on the brick industry struck a chord with me, having just seen photos taken by my partner during his recent foray to India.

In short, Parsons offers a critique on how development has led to increased poverty and even slavery, and the loss of productive lands to industrialization. I found myself furiously scribbling notes as I came across various points he made.

When development devalues degradation

I am not recommending this book because I agree with him, but because it covers a huge area that is not commented on in the media.

Development and the accompanying assumption of poverty alleviation is regarded as a good thing.

It is not considered as adding significantly to climate change and habitat loss, nor the loss of dignity, traditional cultures, independence and the valuing of nature that came with those.

Devolution of production and waste to places like Asia, with barely survivable wages, unsafe conditions and the dumping of garbage, is an invisible cost to lower consumer prices and greater production.

Far too commonly,

toxic waste disposal

is defined as a favor.

Far too commonly, toxic waste disposal is defined as a favor rather than allowing cheap production and, of course, health and environmental responsibilities, to be evaded.

So Parsons starts in the factories of Cambodia, where major chains that brag about green credentials have outsourced both manufacturing and waste of the products they sell. Their factories and compounds force local communities to relocate, the displaced people felling forests and filling wetlands for new villages and farmlands.

In 2015, the United Kingdom developed the Modern Slavery Act which directs companies to declare the absence of modern slavery from supply chains. How many of you see the irony — or should I say fantasy — in this?

Environmental degradation is not a by-product of extraction but the engine of a machine that sucks in materials before exporting and returning waste.

With COP28 being defeated by corporate wealth, this book shows another side to that, equally as damning.

Melody Kemp is a freelancer and contributing SEJournal editor who has lived in and written from Asia for more than 30 years. Her last review was of a book about koalas.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 9, No. 5. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement