SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

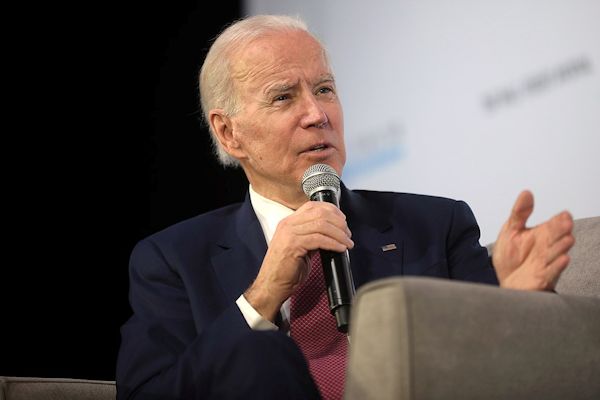

| Presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Sen. Joe Biden, shown above speaking in Las Vegas last Feb. 16, had one of the less ambitious climate change policies. But he has sought to bring young progressives into the fold by embracing a green recovery plan with a more aggressive decarbonization schedule. Photo: Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia Commons. Click to enlarge. |

Issue Backgrounder: ‘Green Recovery’ Policies an Elusive Promise

By Joseph A. Davis

Disasters can be opportunities. Case in point is the calamitous COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting worldwide recession. Could a “green” pandemic recovery, in the end, be good for the public health, the economy and the environment?

It remains to be seen. But key decisions regarding green recovery are being made right now that environmental journalists would be wise to keep a close eye on.

The basic idea behind green recovery is to kill two birds with one stone. In the United States, for instance, COVID-19 relief money Congress is shovelling out could help fund millions of clean energy jobs that would in turn alleviate unemployment, boost environmental justice, foster the energy transition and bring us closer to a climate fix.

But in reality, the green recovery agenda hasn’t made much headway in the United States thus far. That is, unless you’re counting the Democratic party platform, where there’s been a huge success in pushing Democratic candidates toward greater climate ambition (more on that below).

European plan has more ‘flesh on the bones’

Green recovery actually has more currency right now in Europe than the United States.

The strongest voices calling for it tend to be from within the European Union, United Nations leadership, the International Energy Agency and various countries like New Zealand (not that the United States is entirely out of the conversation; it recently joined an IEA discussion on the subject).

Even before the pandemic — back in December 2019 — the European Commission responded by coming up with its own “European Green Deal,” that had a lot more flesh on its bones. Like U.S. notions of a “Green New Deal,” it blended climate action, economic development and an energy transition.

Efforts to get green recovery measures into the three

coronavirus relief bills passed so far by Congress,

for example, have disappointed the policy approach’s fans.

In the meantime, it threatens to fade away or turn into something else. Efforts to get green recovery measures into the three coronavirus relief bills passed so far by Congress, for example, have disappointed the policy approach’s fans. And a fourth big relief bill — currently stalled in negotiations — may prove no greener.

Only if the election gives Democrats the House, Senate and White House trifecta (hardly a given), can we perhaps expect something big.

The Democratic ‘process’

Best not be too distracted by the branding. Barely two years ago, the “Green New Deal” was a thing in the United States — perturbing everybody but lacking the substance or precision of a real climate bill (see our 2019 Backgrounder, "Green New Deal Proposes Sweeping Economic Transformation").

Ever since the Sunshine Movement staged a sit-in in House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office in late 2018 calling for the Green New Deal, the Democratic Party has been trying to find a response. Be sure: Skilled young activists who loudly demand climate action will not drop out of the game.

|

| Participants at a Green New Deal-related sit-in outside Rep. Nancy Pelosi’s office on Dec. 10, 2018. Photo: Sunrise Movement. Click to enlarge. |

Pelosi sidestepped the first onslaught of the Green New Deal without really embracing it. In early 2019, at the dawn of a newly Democrat-controlled House, it hardly embodied the consensus of party electeds.

What Pelosi did do was rather quickly set up the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis and immediately name Democratic members, putting it under the chairmanship of Rep. Kathy Castor (D-Fla.), a centrist compared to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), the Green New Deal’s champion in the House.

Tellingly, that panel was given no legislative jurisdiction. This seemed an effort to quell jurisdictional jealousies from the already-existing committees that did have legislative jurisdiction over climate matters (most notably the Energy and Commerce Committee). The Climate Committee held hearings without making much noise.

Meanwhile, the House Energy Committee, under Chairman Frank Pallone (D-N.J.), struggled to come up with its own climate plan. After hearings, Pallone’s panel in Jan. 2020 emerged with a plan in the form of a bill (that in itself was a step forward). It was practical — but fairly unambitious (for example, it set 2050 as the goal for decarbonizing the U.S. economy).

Much was signalled by the way it came out. It was announced in January, with fanfare, as an “outline.” Only weeks later was it released, with more fanfare, as a bill text. But it was labelled a “draft.” And it was never actually introduced. It was, in effect, a stalking horse, since no Dem climate bill had any prayer of passing the GOP Senate.

In its relative moderation and practicality, it was seen as an alternative to the Green New Deal, which GOPers had been using for some time to beat up Dems. It was also an alternative to a carbon-tax-only approach, which some oil companies and Republicans had been pushing. At the time, it was the only game in town.

Biden climate plan evolves

Meanwhile, the pandemic happened in the first half of 2020, changing a lot of bets (including on Trump’s reelection). By March 2020, Democratic contenders for the presidential nomination were dropping like flies, giving Biden enough delegates to clinch the nomination by June.

Yet of all the candidates in the originally crowded field, Biden had put forth one of the less ambitious climate plans.

Biden’s new problem was to unify

the Democrats and bring back

into the fold the young progressives.

So Biden’s new problem was to unify the Democrats and bring back into the fold the young progressives who had backed progressives like Sens. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), whose climate goals had always been more ambitious than his. Prominent among them were leaders of the Sunrise Movement, who were a big factor in Ocasio-Cortez’s election.

So it was news when Biden on May 13 named Ocasio-Cortez co-chair of the task force aimed at redeveloping his climate position. The other co-chair was John Kerry, who as secretary of state under President Obama had been an architect of the Paris Climate Agreement (which Trump has since said he’ll quit). And it included Varshini Prakash, the 26-year-old co-founder of the Sunrise Movement. The group was part of a “unity” effort aimed at healing the Biden-Sanders split.

Soon after, in June, the Pelosi-made House Climate Committee under Castor released its own final recommendations. It was a massive plan, but only envisioned decarbonization by 2050.

So when Biden’s unity task force on climate unveiled its recommendations around July 8, it was clear that they had moved significantly toward the left-green side — calling for decarbonization by 2035. If, that is, Biden accepted their recommendations.

One big tell came when Prakash issued a statement July 14 signalling clearly that she was on board, although there was “more work to do.”

Biden himself embraced the plan in a July 14 speech (may require subscription).

At that point, the game moved to the platform-drafting effort under the Democratic National Committee, under its chairman Tom Perez. By July 23, a leaked draft of this platform suggested that the party was going to pull up short of the unity task force’s goal, seeking decarbonization only by 2050 — or rather meeting different decarbonization goals between 2035 and 2050.

But it was still ambitious, and as of this writing, still awaits final party endorsement.

It is worth noting some of the bumps left in the Democrats’ climate road.

One is fracking, a bugaboo of the climate radicals. Biden stopped short (may require subscription) of saying he would outlaw fracking, as it was very much an issue in Pennsylvania, a state he badly needed. Nor did Biden explicitly reject nuclear power — a source of carbon-free electricity that progressives rejected.

Pandemic problems

All this while, as the nation sunk deeper into the pandemic depression, much of Trump’s and the Republicans’ political edge was being eroded. Polls showed Trump way down in key battleground states, and GOPers in danger of losing the Senate.

This blunted the power of GOP opposition to climate action. And it presented a very real possibility that come January 2021 Democrats would be able to govern and pass legislation.

As the pandemic unwound in 2020, congressional relief bills inspired frantic and heavy lobbying by all kinds of interests, especially those related to climate and energy. Everybody lobbied. Almost nobody really won.

Environmentalists saw the relief bills as a chance for some “green recovery” prototypes, such as clean energy jobs. Nope. That didn’t happen. But hope remained alive (barely) for extensions of clean-energy tax breaks in the fourth COVID-19 bill, even as chances of its passage grew desperate in August.

Both fossil-fuel-energy and green-energy companies suffered severe hardship as the pandemic wreaked its destruction on the economy. And fossil-fuel-energy companies did reap relief money from the early bills.

But it was hard enough to get the bills through without major policy riders. As Congressional leaders reached for an elusive deal on the fourth relief bill, green recovery was hardly mentioned.

The story is far from over. “Green recovery” may be just a later metamorphic stage of this insect-which-has-yet-to-fly. But it is quite alive. And it could grow wings.

Joseph A. Davis is a freelance writer/editor in Washington, D.C. who has been writing about the environment since 1976. He writes SEJournal Online's TipSheet, Reporter's Toolbox and Issue Backgrounder, as well as compiling SEJ's weekday news headlines service EJToday. Davis also directs SEJ's Freedom of Information Project and writes the WatchDog opinion column and WatchDog Alert.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 5, No. 30. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement