SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

|

| For journalists, understanding how to protect your confidential sources encourages others to come forward, supporting public service journalism and a more informed public. Photo: Kristin Wolff via Flickr Creative Commons (CC BY 2.0 DEED). |

Feature: Want To Protect Your Sources? It Helps To Know the Law

By Chris Young

As a journalist, you know the value sources provide to the journalism you produce every day. Their willingness to share information with you — often on background or off the record — makes it possible for you to pierce the veil of secrecy surrounding government agencies, shine a light on companies skirting environmental regulations and hold public officials accountable.

And their ability to clearly explain complicated issues related to everything from electric vehicles to climate change helps ensure that the information you provide to your audience is not only accurate but accessible.

That’s why you must do everything you can to protect them — for the sake of your journalism and for the public it informs.

From the time you’re a cub reporter,

the importance of protecting

your sources is drilled into you.

From the time you’re a cub reporter in your first journalism job, the importance of protecting your sources is drilled into you by editors. And for good reason. The failure to do so risks scaring other sources from coming forward.

If confidential sources know that their identity could be revealed — risking their job, reputation or even their safety — they might stop talking with reporters altogether. That would mean less public service journalism and a less-informed public.

But sometimes journalists face subpoenas that seek to force them to turn over their notes, documents or other unpublished material, or to testify in court about their newsgathering. What should you do if that happens to you?

A patchwork of protection

Fortunately, most states and the District of Columbia have laws on the books that act as a shield against these intrusions into the editorial process. Known fittingly as shield laws, these statutes make it possible for journalists to challenge such subpoenas.

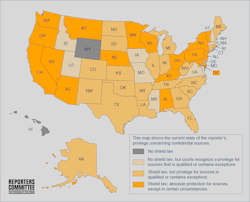

Not all state shield laws are created equal. Some of them offer greater protections than others.

Nevada, for example, has perhaps the strongest law in the country, providing absolute protection for unpublished and published materials, as well as the confidential sources of the information.

|

| Map showing states with and without shield laws. Graphic: Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. |

Other states offer more limited protections, which can vary in strength depending on whether a subpoena is related to a civil or criminal case and whether it concerns confidential or nonconfidential information.

Unfortunately, 10 states do not have shield laws (see embedded map at right). But that doesn’t mean there are no protections for journalists in these states. With the exception of Hawaii and Wyoming, the states without shield laws on the books still recognize some form of a privilege, either through judge-made common law or court rules.

You can learn all about the protections — or lack of — in your state by checking out the “Reporter’s Privilege Compendium.” This handy resource was compiled by my colleagues at the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit organization that provides free legal services and resources to journalists and news organizations.

The compendium even allows you to compare specific provisions of your state’s shield law with those in other states.

The federal gap

Sadly, a federal shield law does not exist.

Despite many legislative efforts over the years — including one measure introduced last year — Congress has repeatedly failed to pass legislation that would create uniform federal protections for journalists from subpoenas, court orders, search warrants and other forms of legal process by federal courts and executive branch agencies.

But there is at least some good news to report at the federal level. In 2022, the U.S. Department of Justice announced that it would no longer use subpoenas, warrants or other investigative powers to compel the production of communications records, work product or other information from journalists who are engaged in newsgathering activities.

The announcement followed dedicated advocacy efforts of a coalition of news media representatives led by Reporters Committee attorneys.

As Reporters Committee Executive Director Bruce Brown said at the time of the announcement, “The new policy marks a historic shift in protecting the rights of news organizations reporting on stories of critical public importance.”

Energy company subpoenas nonprofit news outlet

It might be easy to read about the threats posed by subpoenas and think that it can’t possibly happen to you. But journalists get served with subpoenas more often than you’d think.

Since 2017, in fact, more than 200 journalists have received subpoenas or other legal orders requiring them to testify in court or produce journalistic records or work product, according to the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker. [Full Disclosure: SEJournal Editor Adam Glenn is a deputy editor at Freedom of the Press Foundation, which is the editorial lead and manages the day-to-day operations of the Press Freedom Tracker site.]

And those are just the cases we know about. As the Tracker notes, “Many subpoenas are not publicly reported and legal orders for journalist records are conducted with high levels of secrecy.”

A nonprofit news outlet has spent

the past couple of years fighting a

subpoena issued by the company

behind the Dakota Access Pipeline.

One of the cases currently working its way through the courts involves Unicorn Riot, a nonprofit news outlet in Minnesota that has spent the past couple of years fighting a subpoena issued by Energy Transfer.

In 2021, the pipeline company demanded that Unicorn Riot and one of its reporters turn over emails, audio and video recordings, financial documents and other records related to their coverage of the 2016 Dakota Access Pipeline protests. Energy Transfer filed the subpoenas in state court as part of ongoing litigation.

While the district court correctly held that the records are protected from disclosure under Minnesota’s strong shield law, it still required the news outlet to put together a detailed list of all materials that could fall under the subpoena and explain why each piece should be privileged — a burdensome task for any newsroom, but especially for a small nonprofit.

Both Energy Transfer and Unicorn Riot have since appealed the ruling and the Reporters Committee recently filed a friend-of-the-court brief in support of the news outlet.

In the brief, Reporters Committee attorneys argued that “Attempts by civil litigants to rifle through the notebooks and newsrooms of third-party journalists and news organizations can, among other things, result in costly and time-consuming legal battles that divert journalists’ attention and resources away from reporting, and foster distrust of the news media among potential sources — who may be less willing to speak to journalists.”

Hotline help

The Energy Transfer case is one of a growing number of climate-related legal disputes playing out worldwide. If this trend continues, we could see more instances in which environmental journalists face subpoenas forcing them to turn over their newsgathering materials and reveal their sources.

You obviously don’t want to be one of them. But if you ever happen to be the target of a subpoena, it helps to know your rights. So take some time to familiarize yourself with your state’s shield law before you need to use it.

And if you ever need additional guidance on protecting your sources and newsgathering materials, you can always contact the Reporters Committee’s free legal hotline, which is available to journalists 24/7.

The legal hotline is an important resource for much more than just figuring out how to respond to a subpoena. It's also helpful for navigating a wide range of other media law and press freedom issues, including, for instance, when a police officer tries to seize your camera or search your notes while you're covering a protest.

Chris Young is the editorial manager for the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. Before joining the Reporters Committee, Young taught and advised student journalists at American University. He previously worked as a reporter for Pittsburgh City Paper, Pittsburgh's alternative weekly newspaper; the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit investigative news organization based in Washington, D.C.; and inewsource, a San Diego-based nonprofit investigative news outlet.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 8, No. 46. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement