SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

BookShelf

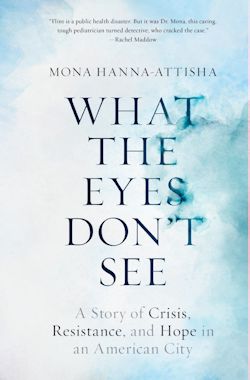

“What the Eyes Don’t See: A Story of Crisis, Resistance, and Hope in an American City”

By Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha

One World, $28.00

Reviewed by Tom Henry

Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha was the pediatrician, scientist and activist who proved that contaminated water in Flint, Mich., had indeed caused a huge spike in the city’s lead poisonings. That gives her incredible insight into what is — at least in modern times — North America’s biggest public health tragedy.

Hanna-Attisha has now written a book about the Flint water crisis that is amazing on many levels, the most obvious being that she has her own great story to tell of her crucial role in bringing worldwide attention to it.

What makes the Flint water crisis so fundamentally sad and wrong in the first place is that Flint saved mere dollars a day by eliminating corrosion control for its water system. In retrospect, that was arguably one of the most misguided decisions ever made by public officials — and was one of many lost opportunities to avert the crisis.

|

Instead of spending roughly $100 a day on chemicals that keep lead pipes from corroding and leaching lead into tap water, billions of dollars must now be spent to replace those lines. And there will be enormous public health consequences for decades to come, especially to children age 5 and younger, who are the most vulnerable.

The decision was made by an emergency manager that Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder had appointed to cut as many corners as possible to help cash-strapped Flint regain some fiscal austerity. The city had struggled for years following a pull-out by General Motors.

But that call, made after Flint switched from the reliable-but-expensive Detroit water-distribution system to the highly corrosive Flint River, defied even the most basic engineering concepts such as those espoused by the Washington-based American Water Works Association. The AWWA, which represents the nation’s water-treatment plant operators, basically argued they should listen to the science and not cut corners on water treatment.

Unraveling the mysteries of water treatment

Hanna-Attisha, who impresses me in this book and in our interviews as a brilliant, highly dedicated and fiercely passionate doctor, admits she knew little about the arcane world of water treatment when the Flint water crisis began.

She was driven to do her game-changing investigation by a high school friend, Elin Betanzo, who at the time was working at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and was drawing parallels between what happened in Flint and a much lesser-publicized tragedy in Washington, D.C. a few years earlier.

The event in Washington was fresh enough in Betanzo’s mind to urge Hanna-Attisha to obtain county data on lead-exposure blood tests required of all children age 5 and under. Lo and behold, the spike that began after the switch to Flint River water was irrefutable.

All of that is gracefully explained in this book, which also has a couple of surprises — such as that the data was harder to obtain than one would think for a pediatrician, and that Hanna-Attisha, now hailed as an international hero, at various points experienced trepidation and anxiety.

For instance, she was surprisingly uneasy at first working with Virginia Tech’s Marc Edwards, a central figure in the D.C. investigation whom Hanna-Attisha describes as somewhat of a rock star in terms of public water research, a scientist whom she said has drawn both praise and controversy.

Edwards and his Virginia Tech students, however, ultimately helped blow the lid off the Flint investigation with tap water data they obtained and analyzed from homeowner faucets.

Hanna-Attisha — who happens to be one of the speakers for the opening night of this fall’s annual Society of Environmental Journalists conference in Flint — also writes about her sleepless nights and initial nervousness in approaching a microphone, especially at the landmark news conference when she revealed her cause-and-effect study results.

She was later hailed for surviving intense backlash from the governor’s office, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality and others motivated to downplay Flint’s problems because of politics.

An immigrant past, an unswerving sense of accountability

Flint is a classic case of environmental justice ... or environmental injustice, environmental racism or whatever term you like best for heaping a disproportionate brunt of an environmental problem on poor people.

Hanna-Attisha brings a fascinating

perspective to her story of Flint

thanks, in part, to her own roots.

Like in the D.C. incident brought to Hanna-Attisha’s attention by Betanzo, the majority of Flint’s population is African-American. It’s often been said that Flint’s lead poisoning would never have happened in more affluent cities, such as Ann Arbor.

Hanna-Attisha brings a fascinating perspective to her story of Flint thanks, in part, to her own roots.

Born in England after her parents left their native Iraq, crumbling under Saddam Hussein’s brutal regime, her family emigrated to the United States when she was a young child. She grew up in a well-to-do family in an affluent Detroit suburb, surrounded by well-educated and successful relatives with strong backgrounds in science and a deep appreciation for social justice.

Hanna-Attisha writes about how she developed an affection for Flint because of her father’s job with General Motors when she was little. She provides a well-constructed overview of Flint, down to its amusingly cheesy and short-lived, post-GM theme park, AutoWorld. In the process, she leaves no doubt there has been a longstanding bond between her and the city.

She also writes candidly about how she was involved in environmental activism as a youth, and never lost that sense of accountability or became jaded by her success as a medical professional.

Would another pediatrician been as thoughtful and determined? Possibly. But she believes her brown skin — along with her hold-’em-accountable activist leanings — helped her empathize a great deal with Flint’s lead-poisoning victims, while developing ironclad science as her wake-up call for action.

And one thing’s for sure: The woman can write. Her book is far from an academic journal, bogged down by heavy-handed scientific gobbledygook. Sure, there are a few moments that require a little patience and an intellect to make sense of some numbers. Now and then, a few long words are thrown at you.

But the reward of Hanna-Attisha’s perspective is worth it.

She and Edwards subsequently became two of Time magazine's 100 Most Influential People in the World in 2016, although they were far from being Flint's only heroes. Besides the two of them, there were activist LeeAnne Walters and U.S. EPA whistleblower Miguel Del Toro, the latter two working with Edwards on collecting water samples. There were many others as well.

But Flint needed someone in its medical community standing up for children the way Hanna-Attisha has, with her mother's heart, her fearless spirit and her deep-rooted sense of fairness.

Tom Henry is SEJournal’s BookShelf editor and created The (Toledo) Blade’s environment beat in 1993.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 3, No. 26. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement