SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

|

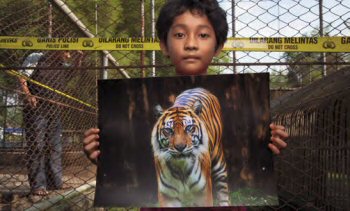

Poachers killed an 18-year-old Sumatran tiger, Sheila, in her cage at the zoo in Jambi, Indonesia the night before this photo was made. Tigers are worth more dead than alive; even a cage in a zoo does not provide safe haven for a tiger when nearly all parts of the cat — eyes, whiskers, genitals, bone, and more — are worth their weight in gold on the black market for use in traditional Chinese medicine. Here, Dara Arista, 8, who came to the zoo to see Sheila, holds a photo of her in front of her cage. The poacher was captured on a bus carrying the tiger parts; he admitted to the crime, for which he was paid $100. |

Between the Lines

Famed big cat photographer Steve Winter and longtime SEJ freelance writer-photographer Sharon Guynup spoke with SEJournal about their book collaboration for National Geographic, “Tigers Forever,” for the second installment of our new feature, Between the Lines, an author Q&A that debuted in the magazine’s Fall 2013 issue. BookShelf Editor Tom Henry reviewed the book (or see page 14 in the PDF for the review and more of Winter's photos) and interviewed the couple before their latest trip to India in December, an 18-day adventure that, among other things, was to generate more video footage for multimedia presentations of their book. Only 3,200 tigers were known to exist in the wild when they began the book in 2012. Now, fewer than 3,000 are left. Said Guynup of the world’s tigers: “They’re disappearing before our eyes.”

SEJournal: “Tigers Forever” was obviously an enormous project, one in which the mysterious big cats were painstakingly photographed over a decade. How did it all come together and what advice do you have for other journalists contemplating a project that involves years of dedication and travel to numerous countries?

Winter: One of the funders said we have to change the way we think about conservation. He said, “Let’s start with tigers and change how we approach it.” It was Sharon’s idea to put all of these stories together. This was all a learning experience for me. [The project] was extremely difficult, but easy in terms of having a lot of habitat destruction and human-tiger conflict to photograph.

Guynup: Let me add that it’s really important to find people on the ground who are working with the experts. Steve has incredible persistence. If I was going to describe Steve in one word, it would be ‘relentless.’

SEJournal: Sharon, how did your role as writer-collaborator differ or complement other major projects you’ve done? What did you find most challenging from a writer’s standpoint when it came to organizing, distilling and packaging the information in a way that tells a story and inspires readers?

Guynup: National Geographic wanted me to write the story in Steve’s voice. In addition to 60-plus tiger experts, I interviewed Steve on numerous occasions. It was a challenge to tell the story in his voice, but also to select some of the key things that happened to him as jumping-off points for the broader discussion about conservation. I had a challenging deadline. I wrote the book in four months and that includes all of the research. I wrote 45,000 words, which includes the profiles and captions. I’m not a crier. But there were so many deeply, deeply disturbing things I heard. I cried a bunch of times writing this book. I was depressed when I finished it. It has made me want to stand up more for the tigers. It has fueled my resolve to get the word out there.

SEJournal: Steve, you pulled out all stops to get the photos, from riding on an elephant to installing camera traps at fixed locations to using mobile, remote-controlled devices. I’ll bet it was, at times, an adrenaline rush – such as when you saw tigers in the wild atop an elephant – and, at times, incredibly tedious – such as when you spent hours installing cameras at a fixed location and not knowing what you’d get. Tell us a little about those highs and lows, how you coped with them mentally and what led to the strategies you used.

|

|

Steve Winter photographing from an elephant’s back in Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve, India.

Photo: © Steve Winter

|

Winter: You’ve got to tell the story visually. Just doing a bunch of cute tiger photos isn’t good enough. A perfect example of that is the book cover photo. I convinced National Geographic to let me go back [and try for a better shot]. When I’m on the elephant, I’m mostly reading books because nothing’s happening. Day after day after day, I’m getting nothing. I had to believe I would never come back until I got what I had gone out to get. It [the cover photo, of a tigress with her cub, taken in the wild from atop an elephant] happened within 10 seconds. Five frames. I used a 600-millimeter (long distance) lens. The cover photo of the book was one frame when there was no movement. The tripod was tied to the box on top of the elephant. Being on the ground in Kaziranga [the national park in Assam, India] was the most stressful thing. It wasn’t just the tigers. I was worried about being attacked by rhinos all the time. We got great photos, but it’s very stressful and very dangerous. I trust the people I’m with. If I don’t trust them, I don’t go with them. You only get to do the elephant from dawn to 10 a.m. or 11 a.m. (in the summer), because it gets too hot for the elephant, like 120 degrees. It’s not a dry heat, either. It’s an oven.

Guynup: You can’t walk through tiger territory or you’ll get killed. You have to either have a Jeep or be on elephants.

SEJournal: Hurricane Sandy struck your New Jersey home as you two began this project. How did that complicate things?

Winter: I had 22 years of field gear downstairs, along with family stuff. I was downstairs moving stuff. I ran up the stairs as the water came in. We lost tons of stuff. Water was spurting in like an old submarine movie and (the door) just exploded.

Guynup: I literally remember doing my first interview (with a source in Asia) on Skype from a motel room, in a Super 8. We were lucky to get a room.

SEJournal: Sharon, “Tigers Forever” is a book that goes beyond identifying a problem. It explains why tigers matter and is a clarion call for action. As a writer, though, you know that readers can get turned off by books that are too sentimental, preachy or agenda-driven. What was going through your mind as you wrote the book, knowing you needed to push the envelope yet strike the right balance?

Guynup: Telling Steve’s field stories – he was in a very remote, very beautiful, but very challenging place. There’s a lot of glamour around National Geographic photographers, but there’s a lot of coming back with parasites. He’s away for long chunks of time. He worked seven days a week, dawn to dusk. Steve is a guy who has really worked hard to tell stories. I’m fascinated by people and culture and history. I tried to weave in all of those aspects as well. You can’t hammer people with an environmental problem (like climate change) without laying out what is being done, what can be done and why it matters. If you’re saving forests, you’re protecting other things (water, air, and wildlife habitat, for example) and it means you’re protecting everything that lives. We’re always saving ourselves [through wildlife conservation]. Tigers are majestic animals that deserve to walk the Earth, but there are wider reasons to save them.

SEJournal: Steve, did you ever feel your life was in danger during this project, not only if you got too close to a tiger in the wild but also because of how much you researched and photographed well-armed poachers and others who may not have wanted you exposing them?

Winter: You could always be in danger of poachers but never know it, because they’re as silent as animals in most cases. One day we came in to check a camera trap and there’s a tiger in a cave and he’s the biggest one in the park. Somebody yells, “Run!” The rules are that if somebody yells run, you don’t question it. You just run. What did that tiger do? He ran in the other direction. They don’t like conflict. But it was stressful. The bottom line is we started getting pictures on the first day. That’s not how it normally happens. That gives you the incentive to go on. It’s like a Crackerjack prize. You never know what you’ll get. You just never know. It’s absolutely incredible when you’re out there. You can’t ever feel too comfortable out there, though. They’re wild animals. You can’t forget that.

SEJournal: What life lessons did both of you get from this project? How did it change you as people and as journalists? How much more did it get you to appreciate the role of conservation officers and the role of the conservation movement in general?

Guynup: There are a couple of people I regard as my heroes. One is [world-renowned wildlife biologist] George Schaller. Belinda Wright [a noted wildlife crime investigator in India] is one of them. So is Debbie Banks, who works for the Environmental Investigation Agency in London [Banks heads EIA’s tiger campaign]. These women are ninjas. They’ve put themselves in danger to get poachers. It’s really amazing. I’ve found it hugely inspiring, personally. This has pushed me into areas I wasn’t comfortable with. I’ve never been a public speaker. It was really, really hard for me to get up on the stage and do that. Since then, I’ve been in a number of other speaking engagements. In my mind, I signed a contract to speak up for tigers.

Winter: With this scientific project, finally, I got the whole package. We have a real body of work here and can talk to the world, as much as we’re allowed to do that – about why we should save their [the tigers’] land so we can save ourselves. This is something we’re going to be doing for a long time to come, talking about saving tigers.

Guynup: Too often as journalists, we go from one story to the next. [With “Tigers Forever”] we have the opportunity to work on a bigger project that can have more impact, one that is intensely satisfying.

Winter: When you do a body of work like this, it doesn’t die in a week or even a month.

SEJournal: What parallels, on a smaller scale, can be made between your ambitious, lengthy project and what many environmental writers do on a daily basis while covering the beat for their hometown publication or broadcast outlet, or when pitching freelance stories?

Winter: There’s something everywhere that’s environmentally relevant. It makes it easy if it’s in your own backyard to make it a long-term project. I know there are environment- or wildlife-oriented stories. We just have to ignite or find the people. You just have to show your editors there’s some meat on the bone and sell them on the stories.

Guynup: Local stories are hugely important.

SEJournal: You said you’ll be expanding this project with more video and multimedia packages. Why is that important?

Guynup: I used to be a photographer. It just seems our profession has become so multimedia, people have become moved by the whole package. I feel blessed to have that strong visual background.

Winter: We have to bring the next generation in, we have no choice. They need video. At the time, we were looking at a book and now need to expand it more with video. [On this latest trip to India], we will get more tiger video and it will go up on the book’s web site.

Guynup: We’re going to keep using whatever medium we can to stick up for the tiger.

For more, see Steve Winter’s interview on CBS News in November or Sharon Guynup’s speech at TEDx Hoboken last summer.

|

|

Although usually found in tropical areas, tigers have a low tolerance for high temperatures and direct sun and seek refuge from midday heat. Here, 14-month-old sibling cubs cool off in the Patpara Nala watering hole in Bandhavgarh National Park, India. |

* From the quarterly newsletter SEJournal, Winter 2014. Each new issue of SEJournal is available to members and subscribers only; find subscription information here or learn how to join SEJ. Past issues are archived for the public here.

Advertisement

Advertisement