SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

BookShelf

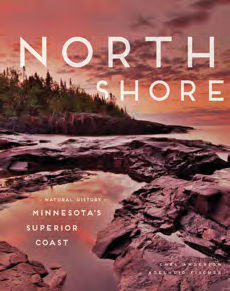

"North Shore: A Natural History of Minnesota’s Superior Coast"

By Chel Anderson and Adelheid Fischer

University of Minnesota Press, $39.95

Reviewed by STEPHANIE HEMPHILL

“North Shore: A Natural History of Minnesota’s Superior Coast” is vast in scope, thought-provoking and poetic in places.

Co-author Chel Anderson has worked in the Superior National Forest since 1974 and made important contributions to the Minnesota Biological Survey. The other co-author, Adelheid Fischer, is a prolific writer and winner of a Minnesota Book Award for Nature Writing.

The book is a celebration of the big and little lives that make Lake Superior and its surrounding region so richly complex, an eye-opening recounting of human errors that have brought the natural systems close to collapse.

The North Shore is not only an ancient place, with exposed bedrock about 1.5 billion years old. It is also an improbably wild place in the midst of the largely settled Midwest.

Nearly every page offers amazing observations.

In the upland headwaters of Lake Superior, for example, the vast Superior National Forest is home to “the highest bird species richness of any region north of Mexico.” Birds save the forest by eating insects.

In the complex web of life in the big lake, tiny crustaceans called mysids are an important link in the food chain. To avoid predators they spend their days near the lake bottom, as deep as 650 feet, but at sunset they migrate closer to the surface to feed on algae. This daily commute uses up huge amounts of energy, and also likely brings pollutants up from the bottom sediments and redistributes them through the water column.

Islands of Lake Superior have their own special ecosystems. Less disturbed than the mainland shore, and bathed in cool, moist winds, they are like remnants of the immediate post-glacial period, and are home to an amazing cast of characters, especially mosses and lichens.

Susie Island, near the tip of the Arrowhead, is thought to shelter 400 species of lichens, and the mosses, in “almost primordial lushness, form a soft, undulating carpet that can grow to depths of three feet,” according to the book.

It is likely Isle Royale was also similarly carpeted, but early copper prospectors set fires to expose the ore, destroying the mosses. The Isle Royale archipelago is the only place in the lower 48 where the sedge darner dragonfly is known to breed.

Reading this book is like being invited along on expeditions in which researchers discover new life forms in the extreme depths, learn how to restore habitat for coaster brook trout, study how changing water levels affect coastal wetlands and observe for a lifetime the relationship between wolves and moose.

“North Shore” is richly illustrated with photographs, maps and drawings. Some of the most intriguing are historic photos of logging, fishing and other human activities that have impacted the lake and its watershed dramatically.

One weakness is the attempt to include Native American perspectives: It would be valuable to hear even more from descendants of the first humans who made their homes on Lake Superior, including a description of their spiritual connection to the waters and their thoughts about the region’s ecological health today.

The book ends with a chapter on climate change. Northern latitudes are expected to warm more dramatically than equatorial regions, and Minnesota is especially sensitive to climate shifts because it sits at a crossroads between the prairie, the deciduous forest and the boreal forest. Moose, lynx and evening grosbeaks are just a few of the imperiled species.

The authors had two ambitious goals. One was to help readers “nurture a deep sense of belonging to nature,” which they achieve by presenting authoritative science in an engaging way. The second was to motivate all of us to “prioritize this ecological knowledge in our decision-making — both in our households and in our communities.”

Stephanie Hemphill is a retired public radio journalist in Duluth, Minn. DISCLOSURE: She made a small financial contribution toward this book’s publication.

* From the quarterly newsletter SEJournal, Winter 2015/2016. Each new issue of SEJournal is available to members and subscribers only; find subscription information here or learn how to join SEJ. Past issues are archived for the public here.

Advertisement

Advertisement