SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

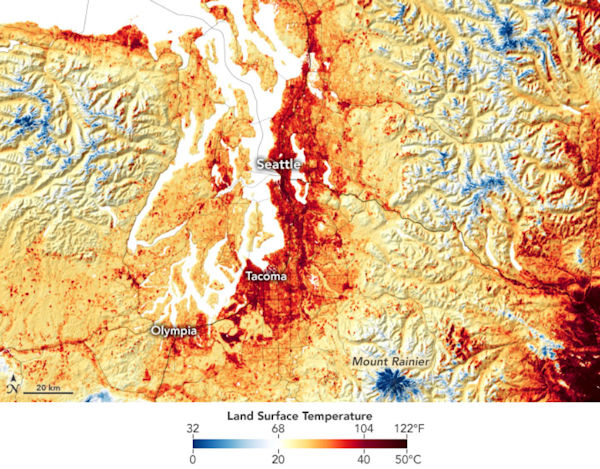

| Land surface temperatures in Washington on June 25, with Seattle reaching 120°F. By the next day, excessive heat warnings were in place across Washington, Oregon and Northern California. Image: NASA ECOSTRESS. Click to enlarge. |

Issue Backgrounder: As Climate Change Brings Extreme Heat Events, Human Health Is a Casualty

By Joseph A. Davis

One sign that we are already in the middle of a climate emergency is the record-breaking temperatures in parts of the United States — and the deaths and health hazards that are coming with them.

Forget for a moment the fires, the hurricanes, the floods, the droughts and the rising seas. The heat itself is an environmental health hazard. And it kills.

The recent “heat dome” that set up over the Pacific Northwest caused hundreds of deaths. Some estimates went as high as 500 deaths in Canada alone. Counts are fuzzy, because methods of counting are fuzzy, which makes extreme heat a silent killer.

This heat often kills the most

vulnerable groups: the elderly, the poor,

the sick, outdoor workers, the homeless.

This heat often kills the most vulnerable groups: the elderly, the poor, the sick, outdoor workers, the homeless and those with inadequate housing. People it does not kill may nonetheless end up in emergency rooms with health crises.

And yes, it has everything to do with climate change (may require subscription). The climate change that is already underway makes extreme heat events more probable, more frequent, longer in duration and more intense. It’s science.

How serious is the threat? We often hear the assertion that extreme heat is the deadliest of all extreme weather hazards (compared to hurricanes and floods, or for that matter, extreme cold).

This is hard to document, because the “cause of death” on a death certificate may not always say heat illness. Often, extensive investigation is needed to make the link. The heat may be a triggering cause of heart or kidney failure when patients have underlying conditions.

So another way to look at a heat event may be via “excess mortality,” often hard to see immediately in crises. In the recent Pacific Northwest heat wave, authorities were reporting “sudden and unexplained” deaths.

Extreme heat event in Pacific Northwest

“Heat wave” may not be a scientific term, but if you are in one you will know it. Intuitively and informally, we understand a heat wave to be a period of at least several days during which the temperature is well above normal temps for the location and season, often accompanied by higher humidity. Or worse.

During late June and early July 2021 in the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia, a regional extreme heat event blew away many all-time record highs. Along with the extreme heat came serious casualties (the numbers are still being investigated and added up). There were at least 107 deaths during late June in Oregon alone.

The village of Lytton, B.C. (pop. 250), set a record for the hottest place in Canada — ever — on June 27 … and then broke that record the next day … and then broke it again the day after that, reaching 49.6°C (121°3F). Then the day after that the whole town was evacuated and went up in flames, killing two people and destroying 90% of the town’s buildings.

Scenes like this were playing out across B.C., Washington, Oregon and more of the Northwest. But the hundreds of deaths weren’t being caused by wildfires. They were caused by the health effects of extreme heat.

The June-July Pacific Northwest

event was just one instance of more

generalized global climate change.

The June-July Pacific Northwest event was just one instance of more generalized global climate change. It is going on across much of the planet, but is more noticeable in areas not used to extreme heat, or areas where geography amplifies heat.

We have recently seen extreme heat in Lapland and the Nordic countries, Siberia and parts of Europe and Alaska. There has also been excess heat in parts of the Middle East that were already very hot.

Understanding heat’s health effects

The human body adapts to heat by involuntary efforts to cool itself, for example, by sweating. When sweat evaporates, it cools the body. This process has its limits. When sweat can not evaporate because of high humidity in the atmosphere, for example, the body starts heating up.

Other factors, like dehydration, can also limit sweating. Bicycle racers drink water constantly and sometimes pour water on their bodies to help cool themselves.

Sweat contains electrolytes (like potassium, sodium, calcium), and when people sweat, they deplete the electrolytes in their bodies. Electrolytes are essential to a number of important bodily functions. When they get too low or out of balance, it can affect heartbeat, muscle contraction, nerve impulses, blood clotting and other important body functions.

The first stage of heat illness is often called heat exhaustion. The symptoms may include heavy sweating; cold, clammy skin; nausea or vomiting; tiredness or weakness; muscle cramps; dizziness; headache; and even fainting.

The first treatment is to get to a cool place, loosen clothes, cool the body with wet towels or a shower, and sip water. If the patient is throwing up or the symptoms persist, it is good to seek medical help.

Sometimes heat illness takes the form of heat cramps — which can be treated by cooling off and drinking sports drinks (which contain electrolytes).

A later and even worse stage of heat illness is called heat stroke or sunstroke, in which the body’s self-cooling systems shut down altogether. It is serious and can be fatal.

The symptoms of heat stroke include high body temperature; hot, red, dry or damp skin; fast, weak pulse; nausea or vomiting; headache; dizziness; nausea; confusion; and passing out. When this happens, you should cool the patient and call 911 right away.

Tracking heat-vulnerable populations

Some people are far more vulnerable to heat illness than others.

The deaths that doctors see during extreme heat events tend predictably to include elderly people, those who live alone or are socially isolated, those who lack air conditioning or other cooling mechanisms, those who have complicating medical conditions like heart disease or kidney failure, and the chronically ill.

The vulnerable include low-income

people who often live in substandard

housing, which may have poor

cooling or lack cooling altogether.

Often the vulnerable include low-income people who frequently live in substandard housing, which may have poor cooling or lack cooling altogether.

Also among the vulnerable are pregnant women, infants and young children, the obese and those taking certain medications.

Especially vulnerable are those who must work outdoors during extreme heat, like athletes, farmworkers and construction workers. They are often unprotected by occupational safety and health regulations.

Less attention, in general, is paid to the ways in which heat stress worsens pre-existing medical conditions, but these, too, are part of the whole picture of heat illness.

Also frequently overlooked as an exacerbating factor is air pollution. Photochemical smog and other forms of air pollution are often made worse by higher heat and humidity — and that raises the risk for people with various respiratory diseases (e.g., asthma).

Preparation, prevention and resiliency

Effective responses to the hazards of heat illness will become more urgent as climate change progresses in coming years — and to places where it was unimaginable before.

Planning and preparation for heat emergencies is something that every community should do. Does your community have a plan?

A range of agencies may be — or should be — involved in heat emergency planning. Those may include fire and police departments, public health departments, hospitals and clinics, weather people and broadcast meteorologists, schools and employers, and others (including news media).

A good plan usually includes monitoring of weather conditions, thresholds for activation, alert systems, safety messaging, cooling centers, neighbor outreach, energy assistance, fan distribution and workplace alerts, among other things.

Overall preventive measures can include changes to the built environment, such as reflective roofs and pavement, green roofs, more trees and installation of cooling equipment, etc.

One result of climate change is that communities that have not historically needed much air conditioning now need it. Has your community anticipated what to do about cooling in the case of a heat-related electric power outage?

Messaging should include key individual behavioral protections, such as activity scheduling, wearing light clothing, drinking plenty of fluids, checking on vulnerable neighbors and keeping pets and kids out of unattended, locked cars.

Some obvious solutions aren’t being implemented — such as occupational health and safety standards for outdoor workers like farmworkers. This is a political problem worsened by industry resistance.

Reporting resources

Some helpful sources of information about the health effects of extreme heat include the following.

- Centers for Disease Control

- Global Heat Health Information Network

- World Health Organization

- National Weather Service

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration, or OSHA

- Local and state public health agencies

- Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA

- Extreme Heat Resilience Alliance

Joseph A. Davis is a freelance writer/editor in Washington, D.C. who has been writing about the environment since 1976. He writes SEJournal Online's TipSheet, Reporter's Toolbox and Issue Backgrounder, as well as compiling SEJ's weekday news headlines service EJToday. Davis also directs SEJ's Freedom of Information Project and writes the WatchDog opinion column and WatchDog Alert.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 6, No. 27. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement