SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

BookShelf: How ‘The Swamp Peddlers’ Scammed Their Way to Florida’s Eco-Destruction

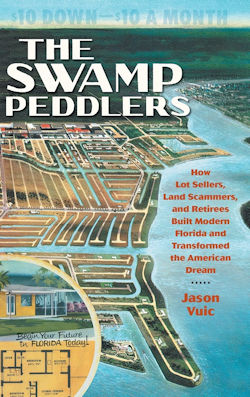

“The Swamp Peddlers: How Lot Sellers, Land Scammers, and Retirees Built Modern Florida and Transformed the American Dream”

By Jason Vuic

University of North Carolina Press, $95.00

Reviewed by Nano Riley

|

Historian Jason Vuic’s latest book, “The Swamp Peddlers: How Lot Sellers, Land Scammers, and Retirees Built Modern Florida and Transformed the American Dream,” is a fascinating look at how old Florida went from acres of pine forests, wetlands and cattle ranches to today’s huge subdivisions sprawling across the state like a cancer, still devouring natural ecosystems.

In the 1950s, Florida’s population was 2.8 million. Miami, still a small Southern city, was just a winter tourist spot. Cubans arrived later.

Elsewhere, the state had few urban centers; the interior was millions of acres of uninhabited prairies of pines and palmettos, home to herds of cattle, and seemingly endless orange groves.

Tampa and St. Petersburg were the only large towns along the Gulf Coast. Naples was still just a small fishing village. Even Orlando was only a business hub for the surrounding citrus and cattle industry.

But all that soon changed, and Vuic does a remarkable job of guiding readers through the schemes that became prototypes nationwide, setting up today’s cul-de-sac society.

Uninhabitable land, carved into quarter-acre lots

Vuic, a historian who grew up in Punta Gorda, recalls the land boom of the 1920s, and boosters such as Barron Gift Collier, a wealthy advertising magnate, who got his name on the county in exchange for funding land improvement. Collier funded the Tamiami Trail, bifurcating Florida, altering the Everglades’ flow.

Beginning in the late 1940s, thousands of returning veterans and retirees willingly bought platted Florida lots, sight unseen. With little oversight, everyone — builders and state officials — lined their pockets. The situation continued for decades.

From Cape Coral and Port Charlotte, to the recent subprime mortgage disaster, Vuic offers a front-row seat for Florida’s growth in a dizzying array of scams.

The scheme proved so successful

it fostered hundreds of planned

communities across America.

Thousands of acres of uninhabitable land, carved into grids of quarter-acre lots, were sold with a classic promotion: For the affordable price of $10 down and $10 a month, average folks could buy their piece of the Florida dream. The scheme proved so successful it fostered hundreds of planned communities across America.

Elizabeth Whitney coined the term “swamp peddlers,” Vuic begins, introducing the lone woman news editor for the St. Petersburg Times (now The Tampa Bay Times) back then.

Her 1970 landmark investigative series about Florida’s development schemes alerted regulators to sleazy practices of hoodwinking buyers. She wrote the series in two and a half weeks to influence a bill to “ban the sale of unusable swampland once and for all.”

That year, Whitney won a Pulitzer.

A litany of unscrupulous acts

Dubbed the “land giants” by Vuic, the two most notable profiteers were the Rosen Brothers and the Mackle Brothers. Both came from the pitch-man culture of the 1950s.

The Rosens hawked mail-order shampoo over the airwaves, creating some of the first infomercials. When that fizzled, the Rosens found Florida.

The three Mackle brothers were already there. They emerged from their service in the war, following their father into the real estate game.

Veterans could get FHA loans; many stationed in Florida were eager to return.

The Mackles’ signature development was Port Charlotte, pioneering the infamous $10 a month for a Florida dream home, far from the snow and ice of the North. Their Deltona Corporation became synonymous with planned communities across the Southwest, not just Florida.

The Rosens founded Cape Coral, hiring dozens of hard-nosed pros who cold-called people relentlessly. Salespeople were told to “take ’em,” the philosophy being if we don’t, someone else will. Many salespeople dropped out: They didn't have the stomach for it, but the pros remained.

The Rosens bought their own fleet of small planes and brought prospective customers down for a weekend. Visitors stayed in the clubhouse, where rooms were bugged to listen in on private conversations. Nothing was left to chance.

Vuic, an author of three previous books, recounts a litany of unscrupulous acts, from the inclusion of high-ranking state officials on real estate boards to blatant fraud.

Longtime Floridians notice problems

In the 1960s, when Gov. Ferris Bryant established the rather toothless Florida Land Sales Board, three of the five members had ties to Gulf American, the Rosens’ corporation.

In the ’70s, some small investors were tricked into buying mortgages not owned by the seller. Foreclosures and vacant houses were a common sight.

Vuic introduces readers to schemers who sold lots impossible to access. Ads for River Ranch, in Polk County, touted “You never had it so good … fun from the very first day,” listing activities: “hunting, fishing, boating, riding and camping.” It’s an investment in Florida real estate, adding that Disney World was expanding to the south.

It doesn’t say, however, that you could live there.

Port Charlotte, the Mackles’ flagship development, was a masterful example of “dredge and fill,” creating land by digging out canals and using the dirt to fill wetlands and marshes nearby.

It was called “fingering.” The law required lots to be more than 3.5 feet above sea level. Though environmentally disastrous, buyers loved it — a boat and a fishing dock right in their own backyard.

Miles of coastal mangrove destruction

replaced with bulkheads and seawalls

destroyed habitat ... Florida was

becoming an environmental disaster.

By the 1970s, longtime Floridians noticed problems. Dredge and fill was finally made illegal. But miles of coastal mangrove destruction replaced with bulkheads and seawalls destroyed habitat; canals carved inland allowed saltwater intrusion. Florida was becoming an environmental disaster.

Vuic’s research is flawless. He has pored over countless documents of land deals, fraud cases, shady practices and outright lies. And for a journalist seeking sources, he provides copious notes.

The final chapter details the transformation of Marco Island from a natural wonder to an upscale community of high-rises blocking beach access. Marco, the largest of the Ten Thousand Islands, is now built out, and it’s hard to realize its pristine beauty before development.

Reading the endless accounts of egregious actions by developers may make environmentalists scream. But, gradually, a few champions arrive. Noted environmental lawyer Nathaniel Reed emerges in the ’70s, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers takes a more active role.

Today regulations have stringent requirements, but there’s lots of restoration to do.

And what about the 1,000 new residents arriving daily? Florida’s future is still uncertain.

Nano Riley is a member of the Society of Environmental Journalists, a journalist, an environmental historian and author of the 2003 book, “Florida's Farmworkers in the 21st Century.”

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 6, No. 36. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement