SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

| The catastrophic potential of hurricanes was brought home by Andrew in 1992. The storm killed 65 people and caused more than $26 billion in damage. PHOTO: NOAA, Flickr Creative Commons |

Backgrounder: Hurricane Season Brings Surprises, and Surprising Depth

By Joseph A. Davis

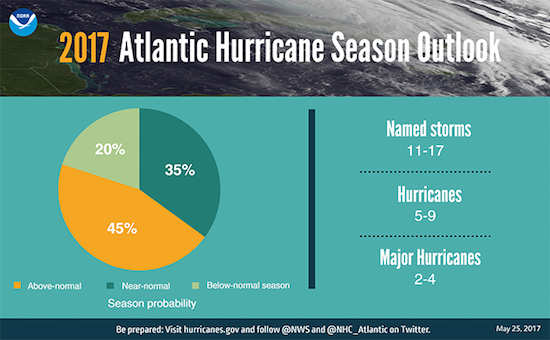

With a slightly above-normal Atlantic hurricane season predicted for 2017, journalists need to get prepared, and quickly.

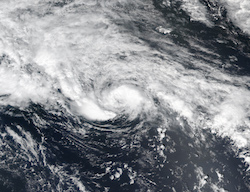

It’s not just because there are surprises — this year’s official June 1 start, for instance, was beaten by weeks when, in April, Tropical Storm Arlene spun up and blew things around in the Central Atlantic without touching land, making the third year in a row that the season has started early.

It’s also important to be ready for a number of new issues that hurricanes raise today but that have tended to get short shrift (or no shrift at all).

For instance, as man-made climate change tightens its grip on the planet, some scientists expect hurricanes to get worse. Also, even as flood-insurance programs drown in red ink, people are building — and rebuilding — in vulnerable coastal zones.

And the intersection of technology and politics matters too. Predictive technologies are getting more skillful, but under President Donald Trump, the threat of budget cuts could make them useless.

Hurricane Katrina in 2005 tried, fatally, to teach us how unprepared we are for major storms, but it is hardly clear that we have learned all the lessons. So here is some hurricane know-how to help your reporting along the way.

Are we overdue for the next “big one“?

We may be at the tail end of a decade-long “hurricane drought,” during which few Atlantic hurricanes made catastrophic landfall in the United States.

That may be just chance, or a matter of definitions. The paths and landfalls of tropical storms or hurricanes are to some extent random, although places like Florida are going to be vulnerable in the end. A map of historical storm track data shows this.

The biggest part of the journalist’s job

is telling the human stories

of people trying to cope with these disasters.

Even in an average year, there is a possibility of an Andrew, a Katrina or a Sandy. We won’t know until a few days before it comes. But each demonstrated the catastrophic potential of hurricanes, even in this modern age (or especially so).

Andrew killed 65 people in 1992 and destroyed over 25,500 homes just in Miami-Dade County, causing some $26.5 billion in damage. Then in 2005, Katrina killed at least 1,245 people and caused property damage of $108 billion. And finally in 2012, Superstorm Sandy was one of the widest we've seen (spanning some 1,100 miles), killing at least 233 people in eight countries and doing some $75 billion in damage.

Here is the list of storm names for the year. Just hope we don’t get to Whitney.

Reporting preparations, recognizing politics

The biggest part of the journalist’s job is telling the human stories of people trying to cope with these disasters. That takes us through many stages — preparation, warning, evacuation, impact, help/rescue and recovery, among others.

Often the stories involve how government and emergency agencies respond before, during and after. And that’s not all of it. Often there is a bigger story of how we make ourselves vulnerable to hurricanes — and how we make the situation worse.

Sandy reminded us of the perils of extensive residential and business development in floodable coastal lowlands. Katrina reminded us of the perils of poorly engineered, maintained and overseen levees.

And don’t forget Rita, in September 2005, which showed the near-impossibility of evacuating several million people from an urban area — as roads became parking lots for tens of thousands of Houston-area residents stuck in 100-degree heat and running out of gas. The Houston Chronicle estimated over 100 deaths were caused by the evacuation alone.

You could talk just as easily about how badly sited and engineered human construction causes fatal landslides. Or how dams poorly built or maintained fail disastrously in hurricane deluges. Or how coal-ash or farm-manure ponds sometimes almost guarantee pollution in hurricane rains. Or how electric power, drinking-water and sewage-handling systems are built without sufficiently planning for hurricane winds and floods.

These are all things that journalists could write about before a hurricane hits.

And, yes, hurricane stories in the end are often political, too. If you doubt it, just ask a New York or New Jersey politician to talk about Sandy. A botched response to Katrina badly damaged then-President George W. Bush.

If you don’t remember New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie’s “hug” of aid-providing President Barack Obama just days before Obama’s 2012 re-election, you can read about it on Breitbart.

And as the 2017 hurricane season started, Congress had yet to confirm Brock Long (although he was confirmed by a Senate panel June 12), Trump’s nominee to head the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the first-line federal rescue agency in hurricane disasters.

|

Does climate change make hurricanes worse?

Nowadays, it has become almost a media cliché to quote some scientist or advocate saying that whatever hurricane is in today’s headlines is a symptom of worsening man-made climate change. There is a point here, but it is rarely quite that simple.

A hurricane is a vast convective vortex that draws its energy from unusually warm sea-surface water — and climate change often does indeed warm Atlantic and Gulf waters above historical seasonal averages. So you would in theory expect warmer climate to amplify hurricanes.

But hurricanes are not simple systems, and their behavior is influenced by a lot of other things. One is wind shear — contrasts in the velocity of prevailing winds at different altitudes — which tends to break up the convective vortex of a tropical storm. Wind shear is influenced by factors other than man-made warming, including the natural oscillation we call El Niño.

You will get a range of opinions from weather and climate scientists about the possible connections between warming climate and hurricanes. One of the deeper students of this problem is MIT’s Kerry Emanuel (who has been the target of vicious threats by climate deniers).

To risk a generalization, some believe that warming climate is likely to bring more intense tropical storms that dump more rain, but not to make storms more frequent or numerous (if anything, the opposite).

One case in point: In October of 2016, Hurricane Matthew killed some 603 people as it careened through the Caribbean and the United States. Climate-change evangelist Joe Romm, writing in Think Progress, cited scientists who thought the evidence suggested a climate cause for the record-setting storm.

It is worth remembering that weather is a complex series of semi-random events that only assemble into patterns when viewed through the lenses of probability and statistics. Thus it is worth being skeptical of statements that causally attribute a specific storm (however intense) to climate change. This is not to say that climate change is not making hurricanes worse.

Do budget cuts threaten coastal residents?

Since Trump has come into office, his administration has proposed a large number of budget cuts to government programs on weather and climate science, and to the satellite-borne data-gathering that makes hurricane predictions accurate (or even possible).

Budget cuts for satellite programs

would leave scientists

(and public safety officials) flying blind

Trump proposed dropping upgrades to the National Weather Service’s computer modeling program — putting U.S. weather models even further behind European and Japanese ones than they already are.

Budget cuts for both NOAA and NASA satellite programs that gather data about the Earth’s atmosphere and oceans would leave scientists (and public safety officials) flying more blind about both climate and weather phenomena like hurricanes. The Environmental Defense Fund, an advocacy group, has objected to these cuts.

Fortunately, at least one key hurricane-watching satellite system was deployed before Trump even entered office. Launched Dec. 15, 2016, NASA’s eight-satellite CGNSS (Cyclone Global Navigation Satellite System) fleet measures wind speed with great accuracy. The system began data production (it’s publicly available) May 22, in time for the start of the hurricane season. CGNSS should improve hurricane prediction.

Timely and accurate forecasting of tropical storms and their tracks has been shown to save lives, allowing earlier evacuations and convincing people of the risks they face.

Storm surge, flooding are major hazards

Sure, hurricane winds (from 74 mph to over 156 mph) are devastating and deadly. But what really gets people into trouble very often is the water. If you are covering hurricanes, water is part of the story.

Storm surges happen when normal sea or estuarine water is piled unusually high by winds and atmospheric pressure differentials — in extreme cases as high as 30 feet above normal. A given storm surge can be amplified by coincidence with normal (or unusual) high tides, by strong wave action and by concentration via coastal landforms.

Coastal communities often locate on very low-lying lands that can be completely inundated by storm surge. Landfalling hurricanes produce surges. This is why we evacuate.

|

| Satellite image of Tropical Storm Arlene, which beat the official start of the 2017 hurricane season by weeks, when it blew up in the Central Atlantic in April. It was the third year in a row the season has started early. IMAGE: NASA |

The National Hurricane Center is among the government agencies that have produced publicly available maps of potential storm surge hazards, which can be viewed interactively online ahead of time. The Center and the National Weather Service will also put out surge warnings as bulletins in real time during a storm.

State emergency agencies also issue surge maps and warnings, such as these from Virginia and Florida. You can also get them from private sector organizations like Weather Underground.

Hurricanes produce huge volumes of rain over large distances inland from the coast. The warm moisture that fuels hurricanes as they develop over the ocean eventually falls as rain when they track inland — which they sometimes do over spans of several states.

Rainfalls of more than six inches in less than a day are fairly common from hurricanes. Rains of that volume and intensity will produce flooding, often flash flooding, with accompanying death and damage. In fact, among all hurricane hazards, inland flooding is the one that kills the most people.

Development in vulnerable areas

You might envy a friend or neighbor’s beach house. But even if it is built up on pilings, it may be at direct risk of damage from coastal hurricane winds, floods and waves — and possible total loss.

It’s not just vacation homes. Superstorm Sandy in 2012 afflicted vast areas of coastal New Jersey and New York — areas where people’s permanent and only homes were located. You can see maps here, here and here.

Just in New Jersey, about 346,000 homes were damaged or destroyed. Also damaged was a lot of public infrastructure such as roads and sewage plants, and natural resources like dunes that can provide some storm protection.

Instinctively, after disasters like hurricanes, many people and governments vow to repair and rebuild — with help from neighbors, insurance, government and banks.

Sandy was no different. People want their lives back. People want to help. State and federal governments put up billions of dollars in aid to help people cope, rebuild and occasionally relocate. The main complaints have been that there is not enough aid (or insurance), that distribution is mismanaged and that it is not coming fast enough.

Four and a half years after Sandy, many victims are still struggling. Journalists have found many opportunities to expose what is wrong with the recovery. Politicians whose careers were built on condemning federal intrusion are often the first to call for federal help.

Sometimes during the Sandy recovery, people have focused on what is called “resilience” — improving communities’ ability to bounce back from such disasters.

For example, the Warbasse housing development on Coney Island has its own water and electricity supply — and rebuilding meant raising the generators and transformers above flood level. On Fire Island, protective barrier dunes are being re-established at considerable cost. In Nassau County, they are building a sea wall around the Bay Park sewage treatment plant.

At a deeper level, though, problems stem from the fact that people — in fact whole communities — have chosen consciously or otherwise to live in harm’s way, and have invested heavily in the structures that support them.

This is not just about Staten Island. Much of New Orleans is actually below sea level, which is not a good place to be during a hurricane or flood. There are other risks on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Over the years there have been recommendations for change in construction standards — which is more helpful for new structures than old ones.

A key premise of the federally supported National Flood Insurance Program is communities are only eligible if they have in place certain kinds of programs to keep people from building new structures in flood-prone areas.

Theoretically, over time, that should encourage people to move out of floodplains and reduce damages. But in practice, things often do not work that way. Damages happen, as Sandy showed. And the NFIP operates under a huge deficit/federal subsidy, now above $24 billion.

Property damage from U.S. hurricanes, statistics show, has been getting worse in recent decades. It may not be because (or primarily because) hurricanes are getting worse. Some researchers say it is because we continue to build more structures in places that are vulnerable to hurricanes.

Expert resources

National Hurricane Center website: This is the real-time “situation room” for both Atlantic and worldwide tropical storm developments. Make it your first stop when storms loom. You can get fast updates via Twitter from @NHC_Atlantic.

National Weather Service media contacts: Here is a set of media contacts for all aspects of weather from the NWS. You may also want to contact your local NWS office.

NOAA media contacts: The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration runs a comparatively transparent and helpful press operation during recent administrations.

National Hurricane Center staff: The NHC, with characteristic transparency, makes public its staff list.

NOAA-NWS Climate Prediction Center: This NOAA office does seasonal hurricane outlooks, and looks primarily at timescales of a year or less.

Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science: A center of research on tropical storms at the University of Miami.

AOML: NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory is in Miami and collaborates with the Rosenstiel School.

Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies: Located in Tallahassee, Fla., at Florida State University, COAPS houses many experts who research a range of topics on air-sea-land interactions, including hurricanes.

NCAR-RAL Tropical Cyclone Guidance Project: In Boulder, Colo., the National Center for Atmospheric Research, funded by the National Science Foundation, is the “Vatican” of climate research. Its Research Applications Laboratory tracks tropical storms.

Weather Channel Hurricane Central: The Weather Channel is a major TV and media outlet devoted to weather. It is all over hurricanes and also does maps.

Weather Underground Atlantic hurricane page: Another multimedia weather news outlet, Weather Underground is a good place to get updated on Atlantic hurricanes.

AccuWeather hurricane page: AccuWeather retails and localizes weather news to many U.S. news outlets. They follow hurricanes predictively.

Gannett/USA TODAY Interactive Storm Tracker: For years, USA TODAY has specialized in graphically and expertly informing people about the national weather picture. Online, they display tropical storm tracks well.

USA TODAY Hurricane Resources: USA TODAY has maintained an archive of the many great explainers they have done on hurricane-related topics over the years. Read and learn.

Chris Landsea/NOAA: A top research meteorologist and hurricane expert, now at the National Hurricane Center.

Kerry Emanuel/MIT: A leading investigator of the connection between hurricanes and climate change.

Thomas R. Knutson/GFDL: A research meteorologist who specializes in hurricanes, at NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory at Princeton.

Phil Klotzbach/Colo. State: The successor of the legendary Dr. William Gray at Colorado State’s Tropical Meteorology Project. A forecast expert.

Rick Knabb/former director, Natl. Hurricane Center: A media-friendly scientist who is now the on-air expert for the Weather Channel on hurricanes.

Joseph A. Davis is director of SEJ’s WatchDog Project, and writes SEJournal Online’s Backgrounders and TipSheet columns.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 2, No. 24. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement