SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

TipSheet: Battles Ahead Over Conservation Fund

If you want to report on how the struggle over federal lands hits close to home in your community, just look at the Land and Water Conservation Fund, or LWCF.

Congress created the fund in 1965, back when parks were more politically popular, and public land was not a four-letter word. The original law authorized a $900 million program to grant federal matching money to federal, state and local land management agencies.

Even in today’s Congress, it embodies the distributive politics of “pork.” A bill with something for everyone tends to get a majority vote.

That also means that wherever you live and report, there is a LWCF story near you. And this year, there will also be fights over national funding levels, state and local conservation projects, federal land acquisition, possible restructuring of the LWCF and probably permanent reauthorization of the LWCF.

Political machinations around program

The money for the LWCF today comes mostly from offshore oil drilling, the political genius of which is that it gives environmentalists and conservationists (not to mention fishers, birders, hunters and hikers) a reason to accept offshore drilling.

LWCF money tends to be focused on projects that enhance outdoor recreation (more genius).

But the politics of federal land ownership and acquisition is rarely tranquil. That was true even before the modern “Sagebrush Rebellion” broke out in the 1970s and 1980s, and long before the Bundys picked up their guns.

The main purpose for much of the LWCF is acquisition of land and water (or rights and easements thereto), so there is a baked-in reason for hostility, especially in Western states, where federal land ownership is often considered oppressive.

But LWCF money can also go to state and local (rather than federal) acquisition — which, again, greases the political skids.

In the Trump era, the LWCF is once more a bone of contention. President Donald Trump’s budget proposal for fiscal 2018 is $154 million — a huge cut from the 2017 level of $449 million.

|

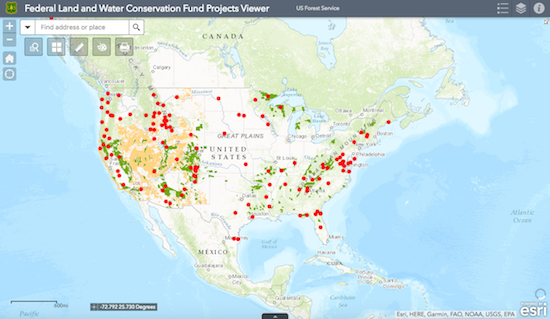

| To find local LWCF stories, reporters can use one of at least two interactive maps that show current projects, such as this one from the U.S. Forest Service. |

In budget-land, that may be academic. Traditionally, many presidents have proposed underfunding programs that are politically popular with Congress members. This is a bargaining ploy because the White House knows full well that members will increase appropriations for programs that benefit their districts. Watch for this when the House Appropriations subcommittee drops its Interior bill soon.

But in today’s GOP-controlled government, this approach is dicier. Congress members unenthusiastic about federal land acquisition actually have power — notably House Natural Resources Committee Chairman Rob Bishop (R-Utah).

Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, while he has said he does not want to sell off federal lands wholesale, has been tasked by Trump with whittling down federal lands held as National Monuments. Zinke, when in Congress, strongly supported LWCF. Bishop actually blocked permanent reauthorization of the LWCF for several years.

In a national political space hostile to public lands, one of the few forces remaining is local political need. Political party leaders in Congress very often make exceptions to their ideological policies for members who need something to please constituents and get re-elected.

Local-ness is another part of the LWCF’s political genius. Much of the federal money must be matched by state and local agencies (a sure indicator of local political support). In some cases, the money even goes to private landowners for preserving the habitat of endangered species.

Funding divided among federal, state agencies

Whatever the federal appropriation for the LWCF, it is divvied up among the states according to a formula set by law.

The money in the LWCF actually goes into several pots.

One pot goes to federal land management agencies, often to acquire land that completes a park or other land conservation unit.

A second pot is set aside for grants to states and tribal governments to acquire or develop conservation lands. (Development, for example, might mean building a playground on an existing park.)

Yet another pot goes to protecting American battlefields, often via grants to state or local governments for land acquisition. The federal agencies that get some funding from the LWCF include the National Park Service, the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the U.S. Forest Service. A more detailed breakdown is here.

LWCF money does not always go just to buy land. For example, it could buy an easement or corridor to allow public access to land (or water) that a government already owns. It could buy a conservation easement (use restrictions to protect endangered species) on land that remains privately owned. It could buy public fishing rights on a body of water.

Long-term Congressional authorization for the LWCF actually expired (for the first time since its enactment) on October 1, 2015 — an event bemoaned by the fund’s many supporters.

Many in Congress blamed Bishop. Bishop openly opposed reauthorization, which his committee has jurisdiction over, calling for reforms that would steer the LWCF away from federal land acquisition and toward more local projects.

But the omnibus appropriations bill Congress passed in December 2015 extended authorization for three years. It is now set to expire in October 2018.

Tools for reporting on the LWCF

Environmental journalists can use several tools to find LWCF stories in a given state or locality. One is a map on the U.S. Forest Service website that shows 2017 projects. The Wilderness Society also has an interactive map showing LWCF projects.

The LWCF Coalition, an advocacy group, maintains a set of state-specific fact sheets on LWCF-supported projects. Most of the material is historic rather than current.

Other groups with a stake in the LWCF are the Wilderness Society and the Izaak Walton League.

One group with a dim view of LWCF reauthorization is the American Energy Alliance. Another is the Heritage Foundation.

Check in with the land conservation and management agencies in your state and ask what current and future projects they hope to fund with LWCF help.

The nonpartisan Congressional Research Service has produced a very informative report on the LWCF, including a historical perspective.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 2, No. 28. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement