SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

Explainer

By JOHN UPTON

|

| Ocean cycles caused by trade winds in the Pacific are to blame for unevenness in an overall upward global temperature trajectory, scientists say. Graphic courtesy of National Centers for Environmental Information, NOAA. |

The planet is enduring an extraordinary jolt.

A 13-year warming lull was recently followed by an unprecedented jump in global temperatures. The temperature spike is coinciding with a surge in worldwide efforts to slow global warming, and it appears to be helping to change the minds of Americans about global warming during a precariously optimistic time for global climate diplomacy.

It’s also presenting reporting challenges for journalists. What exactly is happening, and what’s the clearest way to report it?

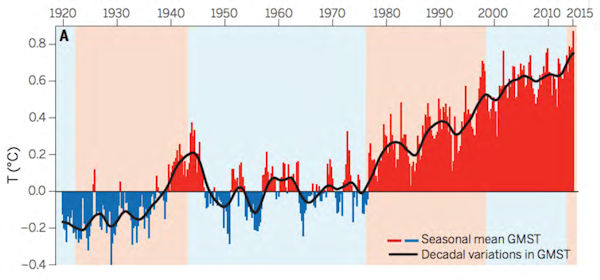

A key concept is that scientists now recognize the importance of slow natural changes in temperature patterns on a “decadal scale” — cycles that can take decades or longer to flip from one extreme to the other.

The so-called “warming pause” from 2001 to 2014 is now understood by scientists to have been caused by natural variation — even as the planet heated unnaturally.

What we know, and what we don’t

Not only was 2015 globally the warmest on record, it beat the previous record — which was set one year prior — by the greatest margin ever seen.

Like most trends that are affected by multiple factors, those of global surface temperatures can seem confounding. Even some scientists disagree about recent patterns. But all of the leading scientists who research them agree about the details that matter to us the most: the planet is warming inexorably, and it is doing so unsteadily.

Journalists need to abandon the notion that a graph of global warming curls steadily upward. It looks more like steps. “Sometimes it’s steeper,” said Gerald Meehl, a National Center for Atmospheric Research scientist. “Sometimes it’s slower.”

From 2001 to 2014, there was a slowdown in warming at the surface of the earth — thermometers at the planetary sweet-spot we call home stopped detecting the type of warming that had been recorded since the 1970s, and before the 1940s.

That 13-year period has been called a “global warming hiatus,” or a “pause,” though neither phrase is accurate. Global warming never paused.

So how to best report it? There are basic facts that can be included in any story dealing with the recent burst of worldwide heat — or with the lull in warming that came before it.

To Paul Rogers, an environmental journalist at KQED and the San Jose Mercury News, the most important line to include is that the ten hottest years on record have been since 1998. “It’s simple and stunning,” he said. That was despite the warming slowdown. “That fact cuts through the complexities of the science and the politics for the public.”

Ocean cycles complicate warming trajectory

Climate scientists blame ocean cycles for the bumps and plateaus in an upward overall temperature trajectory that’s caused by worsening greenhouse gas pollution.

From 2001 until 2014, extra heat that was being trapped on Earth by rising levels of greenhouse gas pollution was being churned into the oceans. That’s because Pacific tradewinds, which loop the southern and northern boundaries of the world’s biggest water body, gusting westward along the equator to weave a figure eight, were blowing more strongly than usual.

For those 13 years, the oceans absorbed an unusually large proportion of the extra warmth that greenhouse gases were trapping on Earth. The surface temperatures were moderated because temperatures in the oceans were increasing. Nearly half of the dramatic ocean warming caused by climate change so far has occurred since 1997, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory reported in Nature Climate Change in January.

The acceleration of ocean warming raised sea levels by corroding ice sheets and expanding the seas.

Then, in 2014, a long-running ocean cycle changed phase, slackening the trade winds. That phase is usually called the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), or the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO).

The most powerful El Niño on record, which arrived a year later in 2015, also ratcheted down wind strengths, fostering heat waves at the planet’s surface and fueling temperature records that have stunned scientists.

“Earth got so hot last month that federal scientists struggled to find words,” the Associated Press reported this spring, after two successive monthly temperature records followed two successive yearly temperature records. “Astronomical,” “staggering” and “strange” were among the words scientists found to describe the records.

“When I look at the new February 2016 temperatures, I feel like I’m looking at something out of a sci-fi movie,” Georgia Tech climate scientist Kim Cobb told AP science reporter Seth Borenstein. “It is a portent of things to come.”

Eventually, the ocean cycles will change phases again. At print time, for example, the El Niño appeared to be giving way to a La Niña. Then repeat, over and over — against a backdrop of accelerating warming caused by greenhouse gases.

Semantics of the “pause”

The cyclical nature of warming has been exploited by fossil fuel companies that fund work to downplay the problem of climate change. That has prompted some scientists to respond in ways that have been challenged by other scientists.

Several teams of scientists have published papers in recent years downplaying the statistical significance of the warming slowdown.

“There is no disagreement that there is decadal variability, and that it is real and needs to be better understood,” said Thomas Karl, a NOAA scientist who led one of those teams.

Karl and other scientists have been derided by their own colleagues for their findings (including in a February op-ed by leading climate scientists in Nature Climate Change) and attacked by politicians, who claim (without evidence) that their research was expedited to support climate rules by the Obama Administration.

The scholarly brouhaha boils down more to perspectives and semantics, however, than it does to meaningful differences in opinion regarding global warming.

One of the papers singled out in the Nature Climate Change op-ed was written by science historian and geoscientist Naomi Oreskes, experimental psychology professor Stephan Lewandowsky and climate scientist James Risbey. The paper was published by the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society last year.

Their paper was largely a call for scientists to use consistent and accurate language when describing the up-and-down warming trend — particularly to stop using the expression “warming pause.” Because there are “frequent fluctuations in the rate of warming around a longer-term warming trend,” it concluded that there was “no evidence” that the recent warming slowdown was unique.

“‘Pause’ has a clear vernacular meaning,” Oreskes said. “Some climate skeptics and deniers have continued to repeat the claim that warming paused, to imply that scientists are wrong about global warming, and therefore we needn’t address it.”

Because concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide continue to rise quickly, global warming’s trajectory continues to be bent ever upward, despite the normal decadal oscillations that scientists are beginning to understand.

There’s no guarantee we’ll see another period in which surface temperatures virtually stop rising. During future slowdowns, temperatures might just rise more slowly. Occasional spurts of warming will almost certainly continue to become more extreme.

Nations taking action, public increasing awareness

Last year was a notable one for the climate — in addition to the temperature record, the world agreed during United Nations negotiations in Paris to attempt a new approach at slowing global warming.

Also in 2014, climate change became a divisive presidential campaign issue. Democrats championed climate rules published by President Barack Obama’s Environmental Protection Agency that underpin commitments the United States made in Paris. Republicans resisted, vowing to undo the EPA rules.

The Paris pact adopts a voluntary and cooperative approach to reducing climate pollution. Nobody yet knows whether it will succeed, but analysis shows the climate actions pledged so far by individual nations are insufficient to achieve the pact’s overarching goal of limiting temperature increases to well below 2°C, or 3.6°F, compared with preindustrial times. (Temperatures have already increased by half that amount.)

With clean energy prices falling, and influential countries growing increasingly concerned about climate change and air pollution, experts hope the Paris pact will foster more ambitious pledges in the years ahead.

Meanwhile, public awareness of the threat of climate change is growing quickly. Gallup polling in March found two-thirds of Americans are now worried about climate change — the highest level since 2008.

Experts attribute rising American awareness to a number of factors, including advocacy by Pope Francis, the high profile of the climate negotiations in Paris and warm recent temperatures, particularly over winter in the U.S. Northeast.

“You expose people to a really hot day or a heat wave or something like that, and many people simplistically say, ‘That feels like global warming, so it must be real,’” said Anthony Leiserowitz, director of the Yale Project on Climate Change Communication.

After a cold snap, though, the opposite can become true again. “Because they don’t have a true understanding of climate change versus local weather, they will then change their view accordingly,” Leiserowitz added.

|

| Warming of the global mean surface temperature (GMST) occurs fastest when the Pacific Decadal Oscillation is in its warm phase (shown in red). The last cool phase of the Pacific cycle (shown in blue) coincided with a surface warming slowdown. Graphic courtesy of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, NSF |

Take care in reporting cycles of warming

Journalists covering climate change have long seen the warming hiatus used in disingenuous attempts to discredit good climate science. Instead of including such baseless claims in stories, the dual roles of climate change and ocean cycles in global temperatures could be briefly mentioned.

It can be helpful for readers to be reminded that global warming doesn’t follow a straight line on a graph.

“We should remember the impact of El Niño and be cautious about trumpeting 2015’s heat as proof of faster warming, only for skeptics to say in 2016 or 2017 that warming has ‘stopped’ if they don’t set new records,” said Reuters climate correspondent Alister Doyle. “A swing to La Niña conditions in the Pacific could mean a cooler year.” That’s natural, even if superimposed over an unnatural longer-term trend.

The relationship between the Pacific Decadal Oscillation and the cycle of El Niños and La Niñas remains unclear, although it appears to be a strong one. If that’s the case, perhaps the two ocean cycles are just climatic ripples in a greater cycle — one that’s so big we have trouble seeing it out in our century-or-so worth of weather monitoring.

That’s why it can sometimes be easiest to settle on just reporting the basic facts: Natural cycles have played important roles in recent temperature records and in the warming slowdown, but the overall trend is of accelerating warming. And that is already worsening heat waves and floods, changing weather patterns and threatening to drown island and coastal communities across the planet.

John Upton is a senior science writer at Climate Central. He has science and business degrees and a decade of international reporting experience.

* From the quarterly news magazine SEJournal, Summer 2016. Each new issue of SEJournal is available to members and subscribers only; find subscription information here or learn how to join SEJ. Past issues are archived for the public here.

Advertisement

Advertisement