SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

| Drinking water pipes in Flint, Mich., where a crisis over tainted water revealed fault lines in the nation’s drinking water system, including funding and financial pressures that are leading some communities to consider controversial privatization of their water infrastructure. Photo: VCU CNS. Click to enlarge. |

Backgrounder: Private Companies Pump Cash from Troubled Municipal Drinking Water Systems

By Joseph A. Davis

If you think of the U.S drinking water system as a network of public utilities, you may want to think again.

Nationwide, as much as 12 percent of the hooked-up population is actually served by private systems, whether nonprofit, for-profit or otherwise. That’s as many as 36 million people.

If any of these private companies are near you, you may well end up covering the issues privatization raises. And you should expect controversy. Like in Baltimore, where the City Council in August voted to ban privatization of any part of the water system within city limits.

Take note: There was also a private water company peripherally involved in the Flint, Mich., drinking water crisis — but while that may make “privatization” sound newsier, the truth is than many other factors were far more important in causing the debacle (see more below).

Still, the Flint crisis offers a viewport on some of the basic problems in drinking water systems in the United States. Operator competence is an issue, for instance. Public officials (like private companies) often prefer to hide and deny their mistakes.

Funding and financial pressure are also key factors. People often can’t afford higher water bills, and if they can, they don’t want them raised anyway.

That was part of the problem in Flint — a city with significant poverty that was being run by an emergency manager because it was essentially bankrupt. Flint customers were required to pay bills (may require subscription) during periods when the water was unfit to drink. Yet Flint customers pay some of the highest rates in the United States.

Small systems can lack key resources

Flint, a city of about 100,000 people, has a water system of significant size. But one big problem in U.S. drinking water stems from the fact that the biggest number of public drinking water systems are much smaller than that.

Small systems often lack the capital investment,

technical expertise and personnel

to deliver good water easily.

While big-city systems with lots of users serve the largest number of people, the biggest portion of the smaller systems serve comparatively few ratepayers. While the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency sets universal basic health standards for water in enforcing the Safe Drinking Water Act, it does allow more leeway for the smaller systems.

But still, those small systems often lack the capital investment, technical expertise and personnel to deliver good water easily. That’s where private water companies can play a role.

For some small communities, privatization may be the right solution. Sometimes private companies will end up owning the water system outright. Sometimes they merely operate it. Sometimes they work as consultants. Sometimes they improve the system’s efficiency. Sometimes not.

Right now, very roughly, there are 50,000 “community water systems” in the United States. Of those, more than half serve 500 or fewer people. Most of the systems in this “small” category are privately owned.

Not all the private water systems are owned by for-profit companies. A 2006 EPA survey showed that of the privately owned systems, 38 percent were owned by not-for-profit entities, and only 22 percent were owned by for-profit businesses. The rest were categorized as “ancillary,” meaning their main purpose was not water supply (e.g., a trailer park).

If only one-quarter of the 36-million private-company customers are served by for-profit companies, one could estimate that less than 10 million Americans get their water from for-profit private companies.

But that same 2006 survey showed that smaller systems are the ones facing the biggest financial strains. Bigger systems usually benefit from many economies of scale. That is one reason (along with urban growth), why there is a trend of smaller systems being absorbed into larger ones.

Problems with the monopoly model

Still, the prevailing “model” is to think of public water systems as “public utilities” — that is, a natural monopoly that serves the public good, and that needs to be regulated not only to protect health but to prevent economic exploitation.

In fact, most of the larger public water systems are owned and operated by cities, counties and other municipal entities (sometimes set up specifically for that purpose).

|

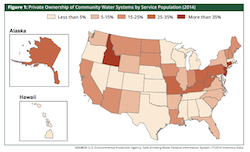

| A map of private water systems across the United States, compiled by the EPA Safe Drinking Water Federal Information System and cited in a recent report by Food & Water Watch, a sharp critic of drinking water privatization. Image: Food & Water Watch report Click to enlarge. |

Natural monopolies result from physical realities: it usually makes sense to have only one set of roads, electric lines, natural gas lines, sewer lines or drinking water supply lines running through a given urban area.

The problem with monopolies is that they have the power to gouge people on prices — hence the need for regulation.

Let’s be honest: Debating the merits of public versus private management is a battleground where intense ideological conflict happens daily in U.S. society.

True believers attribute almost divine wisdom to the “free market,” although companies spend vast sums lobbying to rig the market to their own benefit, and to “run the government like a business” (despite all the bankruptcies).

But by definition, monopolies are not free markets. Therein lies the problem with much drinking water privatization.

Which is hardly to say that governments always act wisely. Far from it. This, too, is part of the problem with drinking water privatization. We have mentioned already that politicians will do almost anything to avoid raising rates (because unhappy ratepayers will vote them out of office).

Pros and cons of going private

But there’s more. For all kinds of reasons, elected and appointed governments often have trouble balancing their budgets — in fact, many struggle constantly to deal with huge deficits.

When a city owns a drinking water system, selling it to a private company offers a huge one-time infusion of cash. The temptation to sacrifice long-term public welfare for short-term political and economic relief may be too much.

A private company can raise rates without blame falling on politicians, and without getting voted out of office. And often they do.

Case in point: Lake Station, Ind. Last year, financially strapped Lake Station sold its system to American Water, one of the biggest players in the private drinking water sandbox. Elizabeth Douglass wrote about the troubles of this town (may require subscription) in a great 2017 piece for the Washington Post. Indiana has more private drinking water systems than the average state, and has passed half a dozen laws making privatization easier.

It may still be too early to tell how the Lake Station decision will play out. But Douglass tells the tales of several other towns who had come to regret selling their systems to private companies — towns like Mooresville and Fort Wayne, Ind., and Missoula, Mont.

They usually have to struggle to get their systems back, sometimes using the power of eminent domain. And they usually have to pay a huge price, much higher than the price they sold it for.

What role did privatization play in Flint?

Ok, so what about Flint? What happened there was awful. There were far more people to blame than we have time to enumerate here, many of them top-level Michigan state officials.

But it was a municipal water system, not a private one. It was a badly run water system, with unaccountable management at many levels, trying to hide its health threats from customers and regulators alike.

Some journalistic accounts have implied

that privatization of water was

a major cause of the Flint crisis.

Some state and federal regulators knew about the lead and covered it up. Yes, Flint in Feb. 2015 let a small consulting contract with Veolia, a private water company, analyze the system’s disinfection byproducts issues. But when Veolia tried to raise issues related to lead, the city told them to ignore lead.

The city was already getting warnings about lead from other channels, and ignoring them. Yet in June 2016, Michigan’s attorney general sued Veolia, trying to make the whole thing seem like Veolia’s fault. It wasn’t.

Nothing has come of the lawsuit. Yet some journalistic accounts have implied that privatization of water was a major cause of the Flint crisis. The evidence suggests otherwise. The Attorney General, Bill Schuette, is now running for governor.

Veolia had a lot more to do with management of Pittsburgh’s system, running it by contract under the oversight of the Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority, or PWSA.

When lead levels started going above health limits in Pittsburgh, it turned out that a big factor may have been Veolia’s alleged decision in April 2014 to switch corrosion control chemicals.

Other evidence suggested PWSA was at fault. PWSA sued Veolia, and the suit was settled in Jan. 2018. It was a no-fault settlement. Veolia no longer manages Pittsburgh’s water.

One recent newsy incident involving a private water company was the contamination of the Charleston, W.V., drinking water by a leak of the coal-washing chemical MCHM in 2014. It may have been just coincidence that a private company, American Water, was running the system there.

Again, there were plenty of parties to blame. But the idea that private companies are always competent may have been belied there. Any competent operator would have taken heed of potentially leaky tanks just upstream of its intakes.

Private water companies tend to claim that they are scapegoated, as Veolia did in both the Flint and Pittsburgh cases.

Problems abound with private companies

Yet there may be many valid complaints against private water companies generally. Let’s look at some.

- Raised Rates. For-profit private companies can and do raise people’s water rates when they take over. A Food & Water Watch survey found that on average, for-profit utilities charged households 59 percent more for water than local governments did.

- Less Accountability. While private companies are still subject to federal and state regulation, they do not allow customers to vote (through elected officials) on how the water system is operated. It matters whether private water utilities are overseen by a state’s public utilities commission. They aren’t always. It’s also worth noting that some of the biggest private drinking water companies operating in the United States are based in other countries. Companies argue there are accountability mechanisms in their contracts.

- Predatory Behavior. When small municipal water systems are struggling to find revenue, make improvements and muster technical expertise, private companies can make an appealing pitch to help them. They may begin merely as consultants, promising greater efficiency. But that relationship can lead to company purchase of the whole system.

- Environmental Justice. Many small towns are surrounded by fringe areas of residents who are often low-income or ethnic minorities. Often these areas are unincorporated. While it may be good for public health to connect these areas to a town’s water and sewer systems, it may also be expensive and not entirely paid for by the revenue they add. For-profit private companies have little incentive to hook these people up. Problems may be worse in poverty-stricken rural areas like some in Appalachia — where extractive industries like mining may already have compromised the water people must drink.

Remember, Flint was a public system and it failed to perform. It is hardly the only public system where rates are too high and public health is harmed.

The perception that public systems are failing is one thing that can drive communities to try private company ownership. So it was in Camden, N.J., which turned to a private company to solve its many water problems. So also in Bayonne, N.J., which found it could only get the financing (may require subscription) for desperately needed system upgrades by turning to a private firm.

The group Food & Water Watch, one of the sharpest critics of drinking water privatization, found in a study that in recent years the trend has been a proportional increase in public water utilities over private companies. That may be partly a matter of urban growth.

Infrastructure issues are key

But privatization is at the heart of some key issues that are unsettled and controversial today. In sum, it’s about our crumbling infrastructure.

Drinking water pipes are hardly the only part of our national infrastructure, but they are a key part — and in many places a very old, failing and underfunded part.

Drinking water systems have taken center stage

in the political drama about infrastructure

that began with the Trump campaign.

Thus, drinking water systems have taken center stage in the political drama about infrastructure that began with the Trump campaign. If Congressional disinterest and inaction is any indicator, the idea that Republicans and Democrats could agree on a jobs-boosting public construction campaign to rebuild U.S. infrastructure is probably pure fiction. Nobody wants to pay.

Instead, Congress plods steadily forward with the old water infrastructure programs, which, however inadequate, do get funded like clockwork. One key example is the EPA Drinking Water State Revolving Fund. That is still getting funded.

Some in Congress were briefly seduced by the Trump assertion that he would personally provide something like $1 trillion in infrastructure funding as soon as Congress figured out a way to pay for it.

Trump’s payment scheme included almost no new federal spending, relying instead on deregulatory magic that would unleash massive private investment instead. One of the essential buzzwords in this pitch was “public-private partnerships.”

PPPs, as the pitchmen call them, are one of the set-ups (there are others) that private drinking water companies use when they take over water systems. They can indeed have the virtue of unlocking big amounts of capital (before raising rates). But they are unlikely to be the silver bullet for many municipalities.

In the end, customers, ratepayers or taxpayers will pay. And it is worth remembering how vast the yet-unfunded drinking water infrastructure needs are in the country. EPA estimates them at almost half a trillion dollars.

Resources for reporting the story

Here are some of the biggest water companies operating in the U.S., each typically operating in many communities.

Larger lists including most others can be found here and here.

Other worthwhile information sources include:

- National Association of Water Companies

- Food & Water Watch

- Environmental Working Group

- Association of State Drinking Water Administrators

- American Water Works Association

- Association of Metropolitan Water Agencies

- Native American Water Association

- National Rural Water Association

- National Council for Public-Private Partnerships

- Value of Water Campaign (industry group)

Joseph A. Davis is a freelance writer/editor in Washington, D.C. who has been writing about the environment since 1976. He writes SEJournal Online's Issue Backgrounders and TipSheet columns, directs SEJ's WatchDog Project and writes WatchDog Tipsheet and also compiles SEJ's daily news headlines, EJToday.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 3, No. 35. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.